If we come to see – or understand – things outside of ourselves differently, we also come to see or understand things inside of ourselves differently, and so find ourselves living differently. When we see differently, we also think and say and behave and feel differently, and often radically so – and hopefully all for the better.

A concrete example of this is the first mariners seeing or understanding, or at least trusting – in the absence of initial, first-hand observations to the contrary – that the earth was actually round and not flat. It changed everything for them; and it changed everything for so many of them, that it changed the world. No more sailing only close to home and taking only the most limited of risks, but letting the sails fly out toward the great unknown and the discovery of that which made the theretofore known world – and in a host of ways – exponentially larger.

The same can be said about other things outside ourselves, things often ignored by our seeing and understanding that could radically alter what’s on the inside and how we go about living life, and especially life for the better. Some of those things I’m referring to are various capacities we can acquire from without that, once acquired and appropriated on the inside, change us, change our place in the world, and so change the world itself. Such as the capacity for courage, the ability to have hope, the capacity to have a certain kind of selfless love, the ability to trust – all capacities, I maintain, that in their largest, most powerful forms are not found inherently deep within us, and so somehow to be uncovered and given life.

Rather, very much like the Christian notion of “the gifts of the Spirit,” I am referring to abilities to live larger and better lives that by their very – almost, if not in fact, supernatural – nature are gifted to us from an authority-and-power outside ourselves that is infinitely larger than who we already are and far beyond any talents, abilities, and capacities we bring to the table.

If, in the end, we fail at life in the ways that truly the matter most to us, it has, in my view, far less to do with what we have failed to do than with our failure to allow another to do those things in us that then give us the ability to be and live larger than we otherwise could be and live.

For a long time I have cringed at the volume of testimonial speeches given at graduation ceremonies and baccalaureate services each spring in which the speaker testifies to an avowed (and rather widely and blithely embraced – almost given – ) notion that “we can accomplish in life whatever we set our minds to accomplish, because all of us have it in us.” The upshot being, then, that “because they did, so can we.”

But we know this isn’t true, because it is a small number of folk who actually accomplish the great things that the speakers talk about accomplishing in their speeches; which means either that the notion that we can accomplish whatever we put our minds to is a lie or that the vast majority of us are failures.

But aside from the fact that only a small percentage of folk are born with the capacities to accomplish these great achievements of success (measured especially in vocational terms), the genuinely greatest accomplishments in life – that are measured by a settled sense of self, by purpose and satisfaction in aspirations toward goodness, and by an abiding sense of well-being, as well as by an unwavering accompaniment of joyfulness – are in fact capable of being accomplished by virtually all of us, with this caveat:

You and I are are able to accomplish the greatest sorts of great things in life not by putting our own minds to it, as they say, but by allowing that One outside of us who is accountable for our very existence to put his or her mind to it within us, granting us that One’s abilities to be far more than you and I otherwise could be in the accomplishments that matter most, which are, by way of example, the accomplishments of being courageous, of having faith in the form of trust, of being hopeful, of living with gratitude, of being able to forgive, and of having love, among other great accomplishments that we come to know are based on capacities that none of us possess by nature.

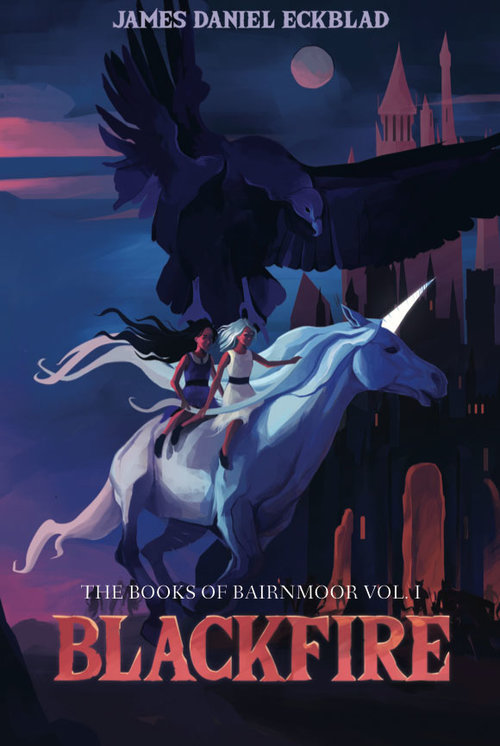

As much as anything, this has been a shaping, if not driving, force behind the creation of the Blackfire Trilogy. And I hope, if I hope for anything at all, that all readers will come away from this novel with an abiding sense that there is an authority and power outside of them that, welcomed within, can gift them with all the capacities required to live their largest and best lives possible.